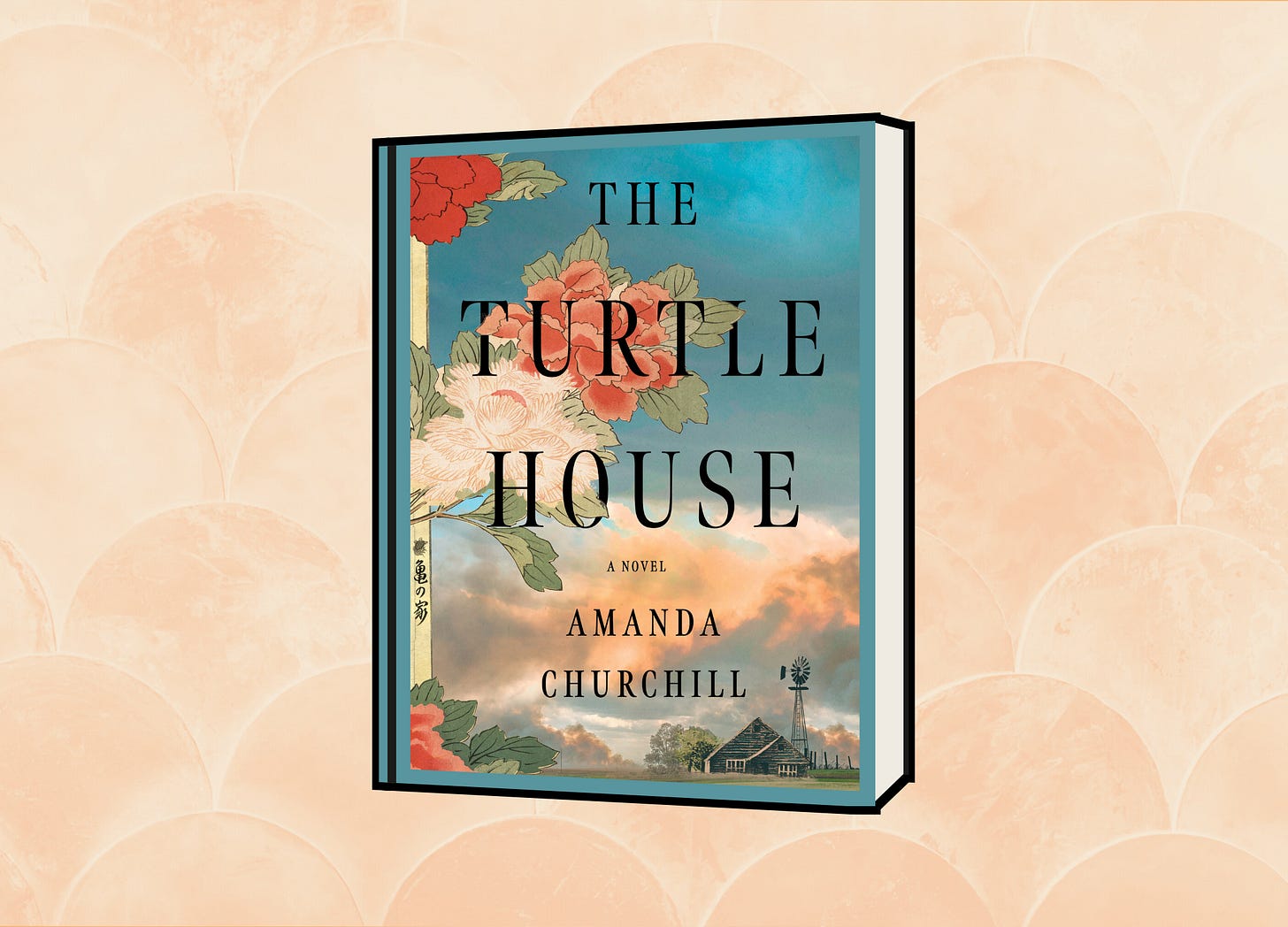

🐢 "The Turtle House" - by Amanda Churchill

A poignant tale of intergenerational connection and rediscovery as a granddaughter learns about her grandmother's past, leading to a joint quest to revive a lost sanctuary in rural Texas.

Hi 👋 and welcome back to my free newsletter where I share a new book chapter every week to help you discover exciting stories.

In this week's edition, you will read an exclusive excerpt of Amanda Churchill’s debut novel The Turtle House.

If this is your first time here, we have an eclectic collection of previously featured novels that you can find here.

Have fun reading! ✨

📚 The Stats

In spring 1999, Lia Cope returns to Curtain, Texas, where she shares a room with her grandmother, Mineko, who moved in after a fire destroyed their ranch house.

Through late-night conversations, Lia learns of Mineko's past as a Japanese war bride, her lost love, and their connection to the Turtle House estate.

As Lia grapples with her own secrets and career choices, she forms a deep bond with her grandmother.

Together, they devise a plan to revive the Turtle House, seeking solace and belonging amidst family upheaval.

"The Turtle House" explores themes of intergenerational friendship, family ties, and the search for home.

🖋️ Quote from the Book:

“What could she want me to do? Or help her do? I’m willing. I have nothing else going on. And I have this need. I can’t even name it. I wonder if this is part of growing older, having needs without names.”

📖 Chapter 1:

Reading time: 9 minutes

Paper hates water. It hates wind. And fire. Paper falls apart. There is no home safe enough for paper, did you know this?

Sometimes my grandmother speaks like an oracle. I mess with the tape recorder settings, make sure the microphone will pick up what she says next, feeling that she is about to tell me something I will need to know, sometime, somewhere.

“And that’s why you’d rather me record you instead of writing everything down?”

“Yes, I like my voice. It’s a good voice, even after all these cigarettes. The doctors say, don’t smoke, Mrs. Minnie-ko Cope, and I say, I do what I want, you old man. Minnie-ko? A man who goes to so much school and who can’t pronounce an easy Japanese name? Sheesh. Mean-echo. Not hard.”

“You can’t expect everyone to know how to pro—”

“You know why I smoke? I like smoking. Cigarettes, very small pleasure. Very small. Home is a place for small pleasures.”

But this house we’re now sitting in isn’t my grandmother’s home. Hers is a half-soggy heap of blackened plaster and ash. She burned it down last month. Accidentally, of course. So she’s living with my parents. So am I. If I’m being honest, I burned down my architecture career. But, I didn’t have a choice. We are both squatters on my parents’ land; eaters of cereal and consumers of ham sandwiches, drifting along out of place. There are nearly fifty years between us: I’m twenty-five, my grandmother is now seventy-three. Today is her birthday. And now we share a bedroom, a tub, a toilet. We tell each other it’s temporary.

My grandmother cracks my bedroom window and sparks a Salem Light, but the smoke comes back at us in a confused rush from a tricky breeze. In response, she hands me her cigarette, opens the window all the way, pops the screen like a cat burglar, and without any hesitation climbs onto the roof. She has already been scolded about this a few times, but scolding doesn’t work on my grandmother.

After the fire, my dad and my aunt fear for her to be alone again, and don’t know where she should live. They chat on the phone late at night. Find an apartment? We’ll just end up moving her again in a few years when she needs more care. Let her live with one of them? She’ll drive us to drink. Move her into a senior living community where they take Saturday trips to casinos up in Oklahoma? She’d hate the people but love the casino. Aunt Mae gently brought up the subject again tonight at Grandminnie’s birthday dinner, and my grandmother shut it down, refusing to discuss any of these options.

“The roof is the most important part of the house, Lia, you know this?”

She is getting situated, carefully settling her rear on the rough shingles, her voice loud on our quiet road. It’s been a rainy spring, and we can hear baby frogs chirping from the water-filled ditches that line Cope Street.

Curtain is small in population and spreads through Dennis County, uneven in shape. It has a downtown, which is just the main drag, the farm-to-market road that runs along the railroad tracks. That one, accurately called Main, has a few perpendicular streets jutting off it. On one side of the tracks, the names are pretty standard, and that’s where the businesses and the churches are—Oak, Pecan, First, Second, and Church. Where they cross the railroad tracks the names change to the names of the people who started the town. Thomas, Whitebrew, Whitehall (don’t dare get them confused, they hate each other), Morris, and Cope. We live off of Cope Street on land that has been in our family for generations. My parents’ house is our “town place”—the “country place” is where Grandminnie lived and where my dad was raised. It was a working ranch until my grandfather died years before I was born.

“Nope. It’s the foundation. That’s the most important part of a house.”

“Yah, little Miss Architect, that’s important, too. But the roof—so much happens under a roof. These shingles are better to sit on than my roof in Japan. Tiles hurt my bottom.”

I contemplate taking a puff off the cigarette before handing it back but don’t, because I suppose I’ve become a woman who just thinks of things and then doesn’t do them. I’m like a squirrel in the middle of a road, doing that back-and-forth thing, holding an acorn. I don’t know what to do next in my life. It’s complicated and shameful. A BA in architecture—the five-year program—from the University of Texas and a career-making job with Burkit, Taylor & Battelle on the team, the one reimagining the skylines of Texas cities. A few months until I had enough hours accumulated to take my Architect Registration Exam ahead of schedule. The apartment overlooking the Colorado River, right at the mouth of Lady Bird Lake, a kayak still hanging in the “ship shack” on the grassy bank just a few steps from my balcony.

Basically, I left my dream. I left live music and tacos and my sweet, goofy roommate, Stephie, who quotes teen movies like they’re Shakespeare. I think of the Colorado, rolling slow and wide and green, my Day-Glo life vest strapped around me as I paddle out. Sometimes, I’d cut through water-skimming fog in my kayak, all those minuscule droplets of cloud against my face. I thought I had everything figured out.

The drag off the Salem burns like a snake of fire down my throat. I have asthma and really shouldn’t be smoking.

I cough from the cigarette and my scalp hurts, which is funny, because no one ever complains of scalp pain, do they? At dinner, my mom ran her hand over my head and picked out a piece of flaky skin, the size and shape of a sequin.

“I’ll buy you some Selsun Blue, baby girl.”

But my grandmother, back in our room, had yanked my head toward her stomach pooch as I sat on the bed in front of her and, her hand on my jaw, her other hand parting my hair in sections, just whistled low and said, quietly, I know this thing you do.

Grandminnie is retired from the Dennis State Home for Mental Impairment. She was a nursing assistant for thirty years and retired last spring.

Her words comforted the dizzying bat-like anxieties swooping and swirl- ing in my brain. Anxieties that make me pick my head until it bleeds.

I remember the way the bats used to fly out from beneath the Congress Avenue Bridge, a black cloud that separated into vibrating clumps like television static. Today, I got a cheery greeting card from Stephie asking me if I’d be coming back or if I wanted her to find a replacement on the lease.

“You are missing Mars! Stop being scarediddy-cat slowpoke-girl!” Grandminnie calls to me through the window. “Hand me my cigarette.”

I thrust her cigarette out the open window toward her. My grandmother is talking to herself about how much has changed on Cope Street in the last forty years.

My window is nestled over the gently angled hip roof that covers the porch, but no fall from it would be gentle. My grandmother does not let this faze her. Her legs are clad in dark gray polyester slacks, and she’s wearing her upstairs house shoes (she has a different pair for downstairs). She is still muscular, stocky. My aunt Mae, my dad’s only sibling and Curtain’s lone pharmacist, in charge of everyone’s blood pressure and rosacea flare-ups, thinks Grandminnie is growing forgetful and going through a regression of sorts. My dad says it’s like a midlife crisis, to which my mom will quietly mutter, Well, hell’s bells.

I carefully perch beside her. The shingles are still warm from the sun, but the air is growing chilly. The pecan tree is budding with dangling yellow-green worms of pollen. It has grown crooked and is so close to the house, I can nearly reach out and touch it. I don’t know many details about my grandfather, not much is said, favorable at least, about the man. But he was fond of his pecans and babied the trees planted by his own grandfather at the ranch. This one is a relative of those ancient trees, stuck in the ground the same year I was born.

“Your daddy needs to look at this roof. Some bad places here. That hailstorm last year! Needs to be replaced, maybe. Also, that tree, it needs to be trimmed. He’s so busy with work, too busy!”

My grandmother isn’t being rude. This is who she is. When I look sloppy, she tells me. If the food’s too salty, she says something. Everything is noted. I used to take offense, but after living with her for twenty-eight days, reaching for the same coffee mug each morning, even sharing some of my clothes, I see now, perhaps for the first time, that she filters life this way. It’s like I’ve slipped into Grandminnie’s skin. This is how she loves, by taking note. Why, I don’t know. My mother says it’s cultural, and my father just usually leaves for work—he’s always working—when Grandminnie gets this way. I think there’s more to it.